Andean healers have long depended on the unique healing properties of the jararanko lizard to alleviate suffering. However, this ancient practice now faces a dire threat as the lizard’s population dwindles, pushing it to the brink of endangerment. Traditional healers emphasize their reliance on this creature, viewing it as their sole source of healing, with no pharmacy or modern medicines at their disposal. Generations have witnessed the therapeutic potential of the jararanko, but as scientists point out, overexploitation may inadvertently harm its population and disrupt the ecosystem. Thus, the delicate balance between traditional wisdom and conservation concerns becomes increasingly pronounced.

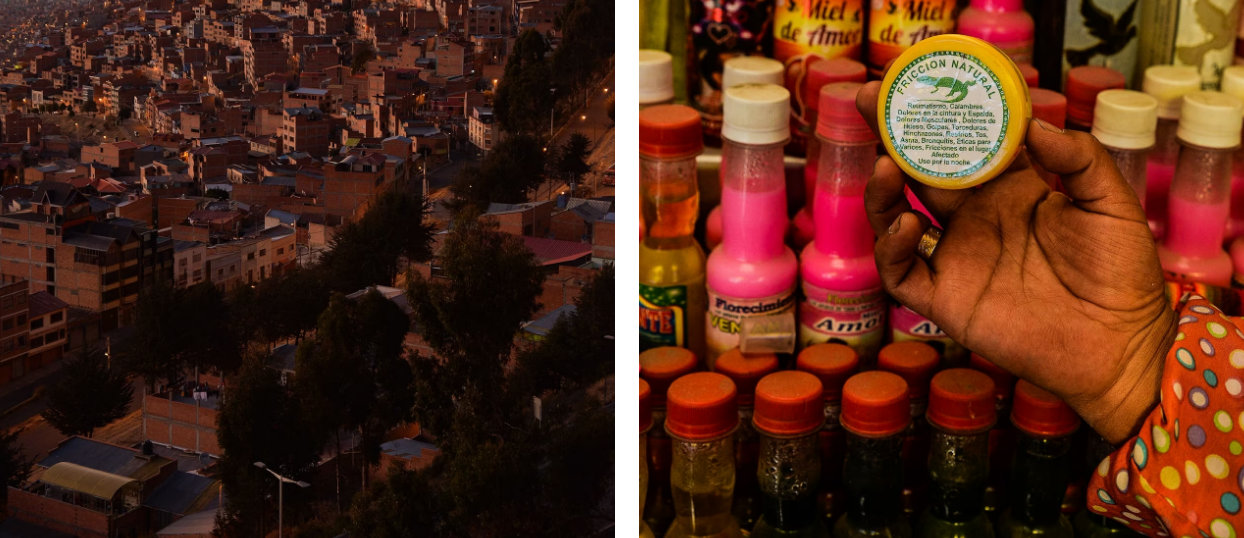

BOLOVIA: LA PAZ In the sun-drenched Bolivian Andes, amidst the stunning snowy wetlands and pristine natural springs, Victoria Flores guides her herd of llamas and alpacas. Amid this picturesque landscape, an olive-colored lizard emerges from its hidden abode.

This six-inch reptile, known as the jararanko in the Indigenous Aymara language, perches on a rock, basking in the warm sunlight. Seizing the opportunity, Flores carefully captures the lizard, swiftly ending its life with a single strike from a stick.

“Sometimes the jararanko can be quite menacing, chasing and even biting you,” admits Flores, who, as an Aymara individual, legally harvests these creatures for their role in traditional medicine.

She employs the ground remains of animals in what she calls a “lizard patch,” a traditional remedy for addressing muscular afflictions. Back in her homestead, she manually grinds the animal’s meat in a stone mill and combines it with native herbs like wichullo, black kettle, and arnica, resulting in a green, pasty substance. This homemade concoction is applied to her injuries, as modern pharmacies and medicines are absent in her remote locale. She relies on the “jararanko,” as she explains. Unfortunately, the dwindling population of the Forster’s tree iguana (Liolaemus forsteri), listed as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and the Red Book of the Vertebrate Wildlife of Bolivia, poses a threat to this practice.

In June 2023, spiritual guides and practitioners of alternative medicine gathered in El Alto, Bolivia’s second-largest city, to pay homage to a mural representing Mother Earth. In a display of deep reverence for nature, individuals made offerings of alcohol and coca leaves at this sacred site. This unique ritual serves as a testament to the strong connection between the people of El Alto and the environment, reflecting their profound spiritual and ecological values.

The Jararanko lizards are indigenous to the elevated valley enveloping La Paz, with altitudes ranging from 13,400 to 16,200 feet. In the city of La Paz, a unique ointment infused with extracts from these lizards is available for purchase at a natural-medicine marketplace. This distinctive product reflects the local biodiversity and traditional remedies of the region, catering to those seeking alternative treatments and embracing the rich natural resources found in the high-altitude terrain.

Exclusive to Bolivia, where it goes by the name “jararanko,” this reptile inhabits the elevated valleys surrounding La Paz, ranging from approximately 13,400 to 16,200 feet above sea level. The species faces threats not only from its collection for traditional medicinal purposes but also from the loss of its natural habitat due to mining and urban development.

Bolivian legislation permits Indigenous communities to hunt this creature for traditional medicine, provided it’s for subsistence within their ancestral lands and follows pre-Spanish invasion customs. However, Bruno Miranda, a biologist affiliated with Bolivia’s Network of Researchers in Herpetology, notes the absence of scientific evidence supporting the reptile’s medicinal attributes. Moreover, these practices may expose individuals to infectious agents, potentially causing zoonotic diseases such as salmonellosis. Miranda suggests a critical reevaluation of these practices in contemporary times is warranted.

The utilization of black-market reptiles, such as Jararanko, as a component in traditional Andean medicine, boasts a rich history, extending back to pre-Columbian eras. This practice, known as zootherapy, was passed down through generations, with Flores recounting how her grandfather employed it to heal injuries. She, in turn, continues this age-old tradition, using zootherapy to treat her own children’s ailments. The enduring cultural significance of these practices highlights their importance in the Andean region, where ancient wisdom and remedies persist in modern times. (Explore the largest global crackdown on the illegal trade of reptiles for further insights.)

In the concealed marketplace of El Alto, a unique concoction blends exotic lizards and rare herbs, offered for sale. This enigmatic elixir is marketed as a potent liniment, sought after for its reputed efficacy in soothing sore muscles, or as valuable ingredients for crafting various medicinal ointments. This clandestine fusion of fauna and flora has piqued the interest of those seeking unconventional remedies, creating a discreet and exclusive niche within the bustling market of El Alto. Its origins and properties remain shrouded in mystery, captivating the curiosity of both locals and travelers alike.

The primary concern in the valley is the influx of outsiders seeking to capture jararankos, which are often transported in drums, ostensibly for sale or medicinal purposes, and may also be featured at the 16 de Julio Fair.

As I strolled through El Alto’s sprawling weekly flea market, spanning approximately 200 city blocks, the waft of smoldering charcoal infused the air with a captivating aroma. Within the vast 16 de Julio market, one of Latin America’s largest, I observed 25 live jararanko lizards available for purchase at four distinct stalls.

My attempt to photograph them was met with a stern admonishment from a woman guarding a glass enclosure housing the live reptiles.

At the entrance of the Kallawaya Ametra traditional medicine center, a sign advertised treatments for various ailments, including dislocations, fractures, fissures, detachments, and more. These treatments encompass coca leaf remedies, ceremonies to rid evil spirits, and rituals venerating protective spirits of communities. Inside, Eleodoro Soto Huacatite, a healer from the Amarete community, hailing from the nearby city of Charazani, extended a warm welcome.

Soto, renowned for preserving ancestral medicinal practices, shared, “Our ancestors, predating the Inca era, practiced traditional, all-natural medicine. I’ve been operating this modest stall for nearly 44 years.

In June 2022, Gumercindo Ticona Lipe conducted a restorative ritual for an anonymous construction worker client in El Alto. Utilizing traditional remedies like jararanko and various ingredients, Ticona Lipe exemplified the practices of an Amauta, a skilled healer. Amautas are sought after for their expertise in advising on the treatment of diverse physical afflictions, including conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, bone fractures, and severe muscular discomfort. This holistic approach to healing continues to be a valuable resource for those in need of alternative treatments to alleviate their ailments, offering hope and guidance through age-old techniques.

Inquiries about “jararanko” reveal a fascinating belief in its remarkable healing capabilities. According to the source, this lizard is said to possess astringent properties that enable it to absorb bruises and aid in the regeneration of fractures and fissures. The process involves grinding the lizard into a paste, mirroring the practices in Flores, and applying it to the affected area for a 24-hour period. Remarkably, individuals claim that the pain vanishes entirely by the following day. This unique method is not only intriguing but also suggestive of a potentially potent traditional remedy for various physical ailments.

Inquiries about “jararanko” reveal a fascinating belief in its remarkable healing capabilities. According to the source, this lizard is said to possess astringent properties that enable it to absorb bruises and aid in the regeneration of fractures and fissures. The process involves grinding the lizard into a paste, mirroring the practices in Flores, and applying it to the affected area for a 24-hour period. Remarkably, individuals claim that the pain vanishes entirely by the following day. This unique method is not only intriguing but also suggestive of a potentially potent traditional remedy for various physical ailments.

A popular practice

Soto acknowledges the legal prohibition on killing jararankos, except for their sanctioned utilization in traditional medicine for subsistence purposes within the ancestral domain. Nevertheless, he holds a dissenting view on this matter.

“I am uncertain why the Parliament deemed it necessary to forbid the use of these animals. The jararanko lizard is a life-saver, particularly in remote areas lacking medical facilities. If you sustain an injury far from a city with no access to medical care, how can you ensure your survival?”

Furthermore, even in regions with accessible modern healthcare services, a significant number of individuals still seek traditional healers, indicating the cultural acceptance of these practices, as indicated in a 2011 zootherapy study.

Zootherapy remains inadequately researched in Latin America, despite its widespread usage, a concern the authors highlight.

This situation not only challenges conservation efforts but also poses a substantial risk to the well-being of numerous human communities.

After being kept alive in a plastic bottle for a period of time, these lizards were eventually killed and combined with herbs as part of a traditional healing rite that took place in El Alto, Bolivia, in the month of June 2023.

Reducing Wildlife Crime

Cracking down on wildlife crime is a priority for Rodrigo Herrera, an environmental lawyer in La Paz, Bolivia, who has experience handling wildlife-trafficking cases. The law clearly establishes that any wild animal being traded can be rescued, and those involved in the trade must face penalties. Society needs to become more conscious and stop demanding products derived from wild animals, such as ointments, as there is no guarantee that these products provide any relief.

In 2015, a vendor selling jararanko parts and ointments at the 16 de Julio Fair was raided by the police and Public Ministry following a complaint from the Ministry of the Environment. The vendor had violated the constitutional exception for harvesting jararanko since he was selling to people outside the Kallawaya nation, with the intention of making a profit rather than for subsistence.

Herrera, acting as the plaintiff on behalf of the Ministry of the Environment, successfully pursued legal action against the vendor. During the trial, it was established that there was no ethnological evidence linking the city of El Alto to any original Indigenous nation. As a result, the vendor was sentenced to three years in jail.

In December 2021, authorities removed 61 jararanko lizards from local markets and relocated them to the Vesty Pakos Biopark, a wildlife rehabilitation center. This biopark had previously received 560 jararankos confiscated under similar circumstances in 2012, according to park veterinarian Fortunato Choque.

Due to increased enforcement, sellers have adapted their methods by displaying only a few animals while keeping the others hidden in their stalls. Furthermore, they have shifted from selling entire animals to crushing them and selling them as creams.

Raúl Rodríguez, the national director of the Forestry and Environmental Protection Police (POFOMA), noted that numerous vendors, often low-income individuals, engage in indiscriminate hunting and subsequent commercialization to make ends meet.

Miranda suggests that part of the solution may lie in environmental education, particularly within the communities involved in the poaching. “Working with children through education is crucial to instill respect for their environment,” she emphasizes.

Returning to the wetland with Flores, where llamas and alpacas graze peacefully, she underscores the vital role of jararankos in her life, stating, “I would advise the authorities not to prohibit it. I’m not saying this to promote the product; the jararanko actually possesses healing properties.”

Miranda, who has conducted a five-year study on L. forsteri in the Bolivian Andes, disagrees, as he has witnessed direct evidence of poaching in areas where rocks were disturbed in the quest for jararankos, coinciding with a decrease in reptile population. “They are an integral part of the ecosystem,” Miranda asserts. “We simply need to learn to appreciate them.